Describe your classroom. Most of us would likely say a professor and a room full of students. Also, a good number might say, with a great amount of certainty, that there is only one voice, talking; the voice of the professor. Sound familiar? Ironically, Korea requires students to be self-expressive except in the classroom. No questions are asked, and no one is willing to volunteer to do a presentation. Have you ever questioned that classroom behavior?

Digging into the Silence

In Korea, seldom do students enthusiastically give a presentation in class. They are also highly unlikely to raise a question during class. It is even hard to see students verbally communication with their professors, except to ask the professor to explain something again or to talk slower. Students know how to raise a question of value in the class, and they are familiar with in-class discussion and that they are free to ask professors questions. However, they see this happening in reality only outside of Korea. In Korea, the old saying, ‘Don’t dare step on your teacher’s shadow’ clearly summarizes how much respect society gives instructors. Uniquely, Korean show their instructors a great amount of respect and empower them high authority, much more than another nations. Recently, this situation has lessened, but students are still uncomfortable with asking questions in class or directly to their instructor. Asking a sharp question could be considered being ‘sassy’ or an attempt to ‘challenge’ the instructor’s authority. Since there is a thin line between questions considered rude and questions that show critical thought, Korean students avoid asking questions.

For some time now, attempts have been made to change this classroom atmosphere. Many intellects point out the advantages of two-way communication in class and suggest the Korean classroom needs to change. Lee Jaesang, Director of Research at ‘Happy Family Making Laboratory,’ said: “The quality needed to survive society in the future is creativity, but without asking questions in classroom, individual creativity will not improve.”1 In an attempt to change the classroom situation, Sookmyung Women’s University offers a Presentation and Discussion class, a requisite course for graduation. In the course, students learn about presentations and how to engage in group discussion. However, students are rarely concerned with the course’s objectives. They feel pressured and some feel fear when they think about the class. There is a well-known joke among Sookmyungians that “‘BalTo’ (short for ‘Presentation and Discussion’ class) is actually short for ‘getting crushed and throwing up’ (when shorten, it’s also pronounced ‘BalTo’).”

Asking Questions: What’s Wrong with That?

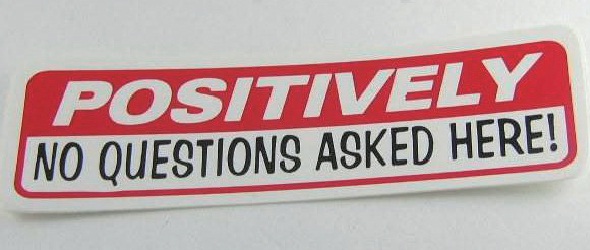

When asked, most students would say that not asking questions in the classroom is a problem. However, have students ever thought about it more seriously? A reporter with Chosunilbo, conducted an interesting social experiment on the ‘no questions asked’ classroom. He visited Seoul National University, Yeonsei University, Jungang University, and Hongik University disguised as a student to observe firsthand the classroom atmosphere. He found out that at each of those four universities not one student voluntarily asked a question, and at only one out of the four universities did the professor ask students a question.2 He found that as soon as the class began, students looked down towards their notebooks and only took notes as the professor lectured. In line with the reporter’s observations, academics have titled this is a one-way lecture. The one-way lecture is problematics since the real meaning of a university lecture tends to get lost. A one-way lecture can be obtained from an online course lecture. Currently, the ‘no questions asked’ atmosphere at university equates to registering for an online lecture, and sadly, sometimes those internet lectures are better than attending a lecture because of the pause and replay function.

In a no questions asked environment, some people feel because they know it all, they don’t need to ask questions in the class. However, it is not possible that not one single student would want to raise a question in class. Whether or not the question a student wishes to raise is closely related to the lecture or not, students typically wish to ask questions. In a democratic nation, it is just not possible for educated people to be void of questions. This 'no questions asked' policy has a few students asking questions after the lectures, but most returning home and wasting valuable time trying to figure it out on their own. Interestingly, this situation is quite common in Korea. The simple survey question: “Despite having a question about the lecture, have you ever just returned home without raising the question and spent hours at home figuring it out on your own?” will most likely result in a majority of ‘yes’ responses, followed by “In the end, I gave up.”

The ‘no questions asked’ policy has turned students into passive learners. These passive students then have a hard time in two-way communication classes. They are not used to that environment, they get nervous when asked questions, and they fear the professor might get offended if they ask. Despite knowing the problems with the 'no questions asked' policy, students are so accustomed to traditional one-way classes that they do not want to change. Joo Heejung, a professor from Jungang University, said, “I grade the activeness of the students, and usually, they are okay with it, but every once in a while, there are anonymous comments saying, ‘The sharing of students’ thoughts is meaningless. It’d be a better class if you would explain everthing.’”3 Despite being shocking, the comment sums up Korean students’ feelings and how many still desire one-way classes.

Not to Solve Problems Like Ostriches

To solve the problem, many universities suggest teaching presentation and discussion or changing the class style to become discussion-based. Others, however, argue that this is useless and only leads to more stress and higher levels of pressure on students. However, the ability to interact with professors in a lively discussion is undeniably something that everyone needs. In 2015, SMT interviewed Seo Gyeongdeok, a person famous for his active non-official ambassador work on promoting and resolving Korean culture and history related issues. He voiced his negative opinion on putting Korean History as a required subject at KSAT, saying that despite studying Korean history, they merely view it as an obligatory curriculum course. Professor Seo Gyeongdeok said, “It’s better than being completely ignorant about the subject. At least they are studying the important subject passionately and ‘know’ the important facts.”4 Enforcing the mandatory registration in a presentation and discussion course will have the same effect. At least the student will attempt to learn.

Donations towards educational change could also help. University students are advanced learners, and as such are more willing to partake in experimental teaching and learning practises. In Jewish education, parents ask their children daily what they’ve studied in class and the mistakes they think they’ve made. Parents then discuss the mistakes by asking why they think they’ve made those mistakes. This type of education in the home by parents would have great benefits. Until that time comes, this type of educations should be included at education donation program. This method might be beneficial because university students learn the importance of questioning, and children will have prior learning experiences with critical thought and questioning at home.

The solution that professors could try is quite simply but complicated. Indeed, professors differ, but many are interested in two-way communication classes. The problem is that students don’t know that professors prefer two-way communication. Therefore, instead of wasting their effort on promoting and teaching discussion, professors need to merely inform students that the course is a two-way communication class. At Sookmyung Women’s University, Professor Hong Gyudeok gave his students his phone number and recommended students contact him through Kakao Talk whenever they had any questions during the course ‘War and Peace.’ This was quite unusual but effective because it made the professor appear much closer to the students and more open to his two-way communication class. A Korean university class cannot drastically change, but with a bit of effort to encourage students to ask questions, students will start to ask questions during lectures in the future.

It’s Normal, Just Begin

“Everyone around the world knows that Jewish education starts with a question and ends with a question. However, not many people know that Israel students were taught how to ask questions. You have to learn how to ask question to be good at it and not asking question means that the education methods are wrong.”5 This was said by Director Rita Ben David, ‘a godmother of Israel science education.’ She is the director of Wolf Prize’s* foundation and what she pointed out tells a lot about the importance of questioning. She pointed out that there were no Korean laureate and suggested an educational environment change. For every reason people give to say that it can’t be helped, the director’s saying proves that it can be fixed and educated. It is normal for Koreans to feel pressured and stressed about learning to question things, but people just need to start.

1. Internet News Team, “[Culture Strolling] University Classroom…,” YoungNamilbo, May 15, 2014

2. Kim Dongyeon, “Universities Without Questions, Will that create…,” Chosunilbo, November 16, 2015

3. Choi Sungwook, “Questions and Discussions Disappeared in…,” Kyosu Shinmun, January 18, 2016

4. The Sookmyung Times no.324, p18-20

5. Park Gunhyung, ““Want A Creative Child? ‘Teach Him/Her How…’”,’’ Premium Chosun, October 27, 2015

* An international award granted in Israel, presented to living scientists and artists regardless of nationality, race, color, religion, sex, or political views